Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria or PNH

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

Definition

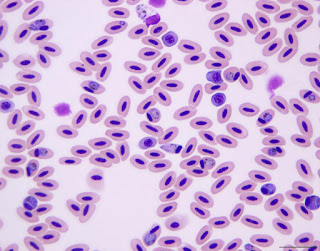

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria or PNH is a rare and chronic disease that results in an abnormal breakdown of red blood cells. PNH is due to a spontaneous genetic mutation that causes red blood cells to be deficient in a protein, leaving them fragile. Because the kidneys help to filter out waste products from red cell breakdown, when urine is concentrated overnight as a person with PNH sleep, the morning urine may be reddish to a darker, cola color.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

This led to term the problem as “nocturnal.” One of the red blood cell products that the kidneys metabolize into the urine is hemoglobin. Because urine discoloration occurs irregularly due to physiological changes, the disease was thought to occur irregularly and so was termed “paroxysmal”.

History

The syndrome of PNH was first recognized in the second half of the nineteenth century. Paul Strübing differentiated PNH from both paroxysmal cold hemoglobinuria and march hemoglobinuria. He concluded that the hemolysis was intra-vascular and did not occur in the urine or kidney.

He theorized that PNH red blood cells (RBCs) were especially sensitive to sleep-induced acidosis. The name, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, was given to this disease by a Dutch physician, Ennekin, in 1928.

In 1911 another Dutchman, van den Bergh, showed that in PNH the RBCs became lysed upon exposure to CO2 in either the patient’s serum or in normal serum, indicating that the PNH RBCs were abnormal. He also demonstrated that hemolysis was dependent upon a heat-labile serum factor.

Incidence

This is a very rare genetic disorder, occurring in only 1 to 2 out of one million individuals. The condition affects males and females alike. Twenty-five percent of the PNH cases in females are diagnosed during pregnancy which increases the death risk of both the mother and child significantly.

Breakdown of red blood cells

Pathophysiology

- GPI is a glycolipid moiety that anchors scores or different proteins to the cell surface. There are more than a dozen GPI anchored proteins (GPI-AP) on human blood cells. CD59 and CD55 are GPI-APs that serve as important regulators of the complement cascade.

- Their absence on the surface of PNH cells explains most of the clinical manifestations of PNH. Hemolytic anemia in PNH results from the increased susceptibility of PNH erythrocytes to complement.

- CD59 and CD55 act at different levels of the complement cascade. CD55 blocks C3 convertases, and CD59 blocks the addition of C9 into the terminal membrane attack complex.

- Thus, the absence of CD55 and CD59 on PNH red cells allows C3 and C5 convertases to proceed unchecked and ultimately leads to increased deposition of membrane attack complexes on the red cell membrane.

- This results in lysis of the red cell and release of free hemoglobin and other cell contents (e.g., lactate dehydrogenase [LDH]) into the intravascular space.

Types

The disease is divided into three categories depending on the context of its diagnosis:

- Classic Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria: Evidence of this condition in absence of some other bone marrow disorder.

- PNH present in the setting of another particular bone marrow disease.

- Subclinical Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria: PNH abnormalities present on a flow cytometry report without any sign of hemolysis.

Causes

- People with this disease have blood cells that are missing a gene called PIG-A. This gene allows a substance called glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI) to help certain proteins stick to cells.

- Without PIG-A, important proteins cannot connect to the cell surface and protect the cell from substances in the blood called complement. As a result, red blood cells break down too early. The red cells leak hemoglobin into the blood, which can pass into the urine. This can happen at any time but is more likely to occur during the night or early morning.

- The disease can affect people of any age. It may be associated with aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, or acute myelogenous leukemia.

Symptoms

Due to the wide spectrum of symptoms associated with PNH, it is not unusual for months or years to pass before the correct diagnosis is established. Overall, the most common symptoms of PNH include:

- Significant fatigue or weakness

- Bruising or bleeding easily

- Shortness of breath

- Recurring infections and/or flu-like symptoms

- Difficulty in controlling bleeding, even from very minor wounds

- The appearance of small red dots on the skin that indicates bleeding under the skin

- A severe headache

- Fever due to infection

- Blood clots (thrombosis)

Other issues include abdominal pain crises and back pain. The classic symptom of bright red blood in the urine (hemoglobinuria) occurs in 50% or less of patients. Frequently patients notice their urine is the color of dark tea. Typically, hemoglobinuria will be most noticeable in the morning, and clear as the day progresses.

Complications

- The most common cause of death in PNH is thrombosis, occurring in approximately 40% of patients.

- These thromboses predominantly occur in the venous system in typical sites, such as deep limb veins, with consequent pulmonary emboli, but characteristically also at atypical sites, such as the hepatic, mesenteric and cerebral veins.

- The risk of arterial thrombosis is also elevated, with increased occurrences of MI and stroke.

Diagnosis and test

Tests required

Complete blood count with differential

Virtually all patients will have depression of at least one hematopoietic lineage (anemia, thrombocytopenia, or neutropenia).

Reticulocyte count

Usually elevated in patients with classical PNH, but often low in patients with AA/PNH.

LDH

Often markedly elevated (five to ten times the upper level of normal) in patients with classical PNH. Maybe normal or only mildly elevated in patients with a granulocyte clone size of less than 30%.

D-dimer

Elevated in patients with ongoing thrombus formation. Elevated levels should prompt further clinical evaluation for thrombosis if clinically indicated and consideration for anticoagulation.

Bone marrow aspirate, biopsy, iron stain, and cytogenetics

Patients with classical PNH usually have a normocellular or hypercellular bone marrow with erythroid hyperplasia. Stainable iron is often absent. Erythroid dysplasia due to the robust red cell turnover is not uncommon in PNH. A small percentage of PNH patients will transform to MDS or acute myeloid leukemia; thus, karyotypic abnormalities are found in a small percentage of patients.

Liver function (serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase [SGOT], serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase SGPT], direct and indirect bilirubin)

Indirect bilirubin and elevated SGOT are common in patients with intravascular hemolysis. Elevation of the direct bilirubin (especially in conjunction with ascites) should lead to an evaluation of hepatic and portal veins with ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Renal function (blood urea nitrogen [BUN] and creatinine)

Usually normal, but acute and chronic renal failure may occur in patients with large amounts of intravascular hemolysis.

Serum iron/total iron binding capacity/serum ferritin

Maybe useful to help assess iron stores which may be reduced, due to intravascular hemolysis.

Imaging studies for diagnosing paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- Imaging studies are not routinely performed. However, in patients describing intractable headache or severe abdominal pain, with or without increasing abdominal girth, imaging studies to help rule out thrombosis may be indicated.

- Abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (listed least to most sensitive), can be used to detect abdominal vein thrombosis.

- CT or MRI may be used to detect intracranial thrombosis.

Treatment and medications

Most treatments for PNH aim to ease symptoms and prevent problems. Your treatment will depend on how severe your symptoms and disease are.

If you have only a few symptoms from anemia, you may need:

- Folic acid to help your bone marrow make more normal blood cells

- Iron supplements to make more red blood cells

Other treatments include:

Blood transfusions: These help treat anemia, the most common PNH problem.

Blood thinners: These medicines make your blood less likely to clot.

Eculizumab (Soliris): The only drug approved to treat PNH, it prevents the breakdown of red blood cells. This can improve anemia, lower or stop the need for blood transfusions, and reduce blood clots. It can make you more likely to get a meningitis infection, so you may need to get a meningitis vaccine.

Bone marrow stem cell transplant: This procedure is the only cure for PNH. To get one, you’ll need someone healthy, usually a brother or sister, to donate stem cells to replace the ones in your bone marrow. These are not “embryonic” stem cells.

If your PNH doesn’t get better with usual treatments, you may want to ask your doctor if you can take part in a clinical trial.

Prevention

There is no known way to prevent this disorder.

Comments

Post a Comment